Carolina Memorial Sanctuary photos by Tom Bailey

Only a half-dozen green burial cemeteries in the US are certified conservation grounds. One of them is Carolina Memorial Sanctuary in Mills River, North Carolina. It's also quite new, having opened up in 2016.

With over 125 natural burial cemeteries in the US, many of them certified as hybrid or natural, what makes conservation cemeteries so rare?

The Green Burial Council, which sets standards and certifies, requires them to "Operate in conjunction with a government agency or a nonprofit conservation organization that has legally binding responsibility for perpetual enforcement of the easement and must approve any substantive changes to operational or conservation policies that might impact the ecological objectives of the site." Land trusts are notoriously leery of the arrangement because the trust becomes responsible for the cemetery maintaining preservation standards and is financially liable if it doesn't. This kind of legal agreement goes well beyond simply specifying green burial on a cemetery deed. Greensprings Natural Cemetery Preserve on 130 acres of land in upstate New York has been working out the kinks to be certified for years.

Conserving Carolina holds a conservation easement on the Sanctuary property. That fact isn't obvious in a visit like my husband and I took. So what else is different about Carolina Memorial Sanctuary? It's also following another GBC requirement that to achieve conservation status a burial ground must "conserve or restore a minimum of 10 acres, or 5 acres if contiguous to other protected lands."

What do the verbs "conserve" and "restore" actually mean? According to Merriam-Webster conserve is to keep in a safe or sound state and would apply in a nature preserve when you have a landscape, such as a forest or meadow, that is already in a desired state. To restore is to bring back to or put back into a former or original state.

Carolina Memorial Sanctuary is fulfilling its conservation status guidelines through restoration.

I visited New Zealand several years ago where the residents actively restore forests to their original state by rooting out invasives like pinus radiata trees, an "exotic" species imported from California and used to rehabilitate previously farmed soils. I saw hillsides where whole groves of trees had been cut down to give native species a chance to grow back. Mass spraying by helicopters is also used. But the key will be whether native plants regrow or simply other exotics.

Our tour guide at Carolina Memorial Sanctuary was Anthony Pranger, an Oklahoman who described himself as the cemetery's "outdoor employee." He is intimately familiar with the land and views it with affection. The 11+ acres, divided between burial and preserve as a conservation cemetery should be, include a number of different ecologies: meadow, creekside, semi-wooded and woodland for burial, and a wetland habitat which is part of the overall conservation effort and not used for burial. It must also preserve, enhance, or restore a historic native or natural community of the region. Carolina Memorial Sanctuary is actively restoring its land to a "natural community." In the past it was used for raising cattle.

The Sanctuary employs three techniques in restoring habitats: 1) removing non-native and invasive plant species; 2) uncovering and protecting desirable species; and 3) planting additional desirable species in areas where they may serve multiple functions (beauty, memorial of a loved one, shade, interest, education). A variety of techniques are used to manage invasive plants, including targeted herbicides, controlled burns, and manual/mechanical and biological controls.

"It's exciting to see the biodiversity of our unique location. I have personally verified over 80 different native plant species and am still discovering more. Watching what birds, insects, and other critters show up, seeing the landscapes change on a daily basis, and engaging the many naturalists who come with an interest in our project."

I asked Anthony to name the more "interesting" species: Sourwood, Sassafras, Persimmons (a smaller native shrub version, not the Asian kind you see at markets), Shingle Oak, Silky Dogwood, Bluestem grasses, Pink Muhly (another grass), St. John's Wort, Creeping Cedar (actually a large club moss rather than a "cedar"), and probably at least 10 different species of aster, including goldenrod, fleabane, and Rudbeckia.

Joe Pye weed was flowering during my visit, doing its job of attracting swallowtail butterflies. It was a hot, overcast morning and I was grateful for the golf cart that Anthony drove us around in, though usually I would have resisted being separated from the landscape.

Carolina Memorial Sanctuary began as an offshoot from founder Caroline Yongue's work with the Center for End of Life Transitions. “Helping people prepare for death and assisting with afterdeath care showed me we were missing a vital element in Western North Carolina: a way to deal with the body that was environmentally friendly and would allow loved ones to participate,” Caroline said to me in an email. The Sanctuary is on land once owned by a Unity church which sits on the border. The church wanted a cemetery but didn't want to run one. The conservation burial ground is open to the public of all faiths. Burial can be in a biodegradable casket or simply a shroud, and families may participate in opening and closing the grave. “It’s not necessarily rustic, it’s just natural--not polished but very welcoming and comforting,” says Caroline.

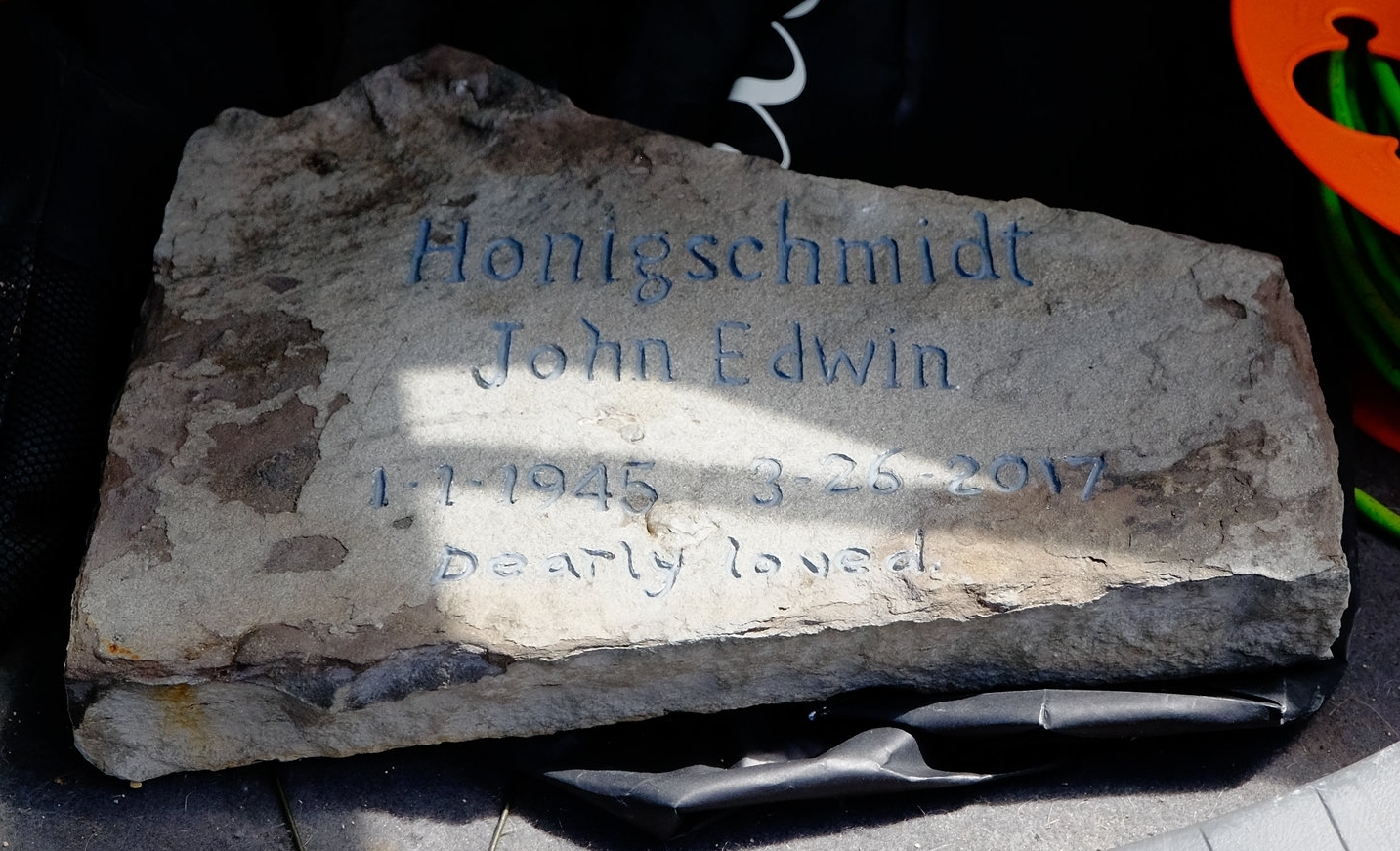

photo by Dan Bailey via Carolina Memorial Sanctuary

One of those buried on the grounds is an artist and teacher. He had cancer when he bought his plot, one of the first to do so at the Sanctuary. He decided to stop his treatments and "move on." Before burying his body his art students painted his body with colored clay.

"We are still fairly young in terms of our time spent on this project," says Anthony, "but we are working towards building a public park made of native landscapes that is also a peaceful and natural place for reflection, grief processing, and dignified burial of friends and loved ones."

Being a new burial ground Carolina Memorial Sanctuary hasn't buried many bodies yet, but it has sold over 130 plots, including pets and humans, full-body and cremains.

One of those plots holds the cremains of a man who had his ashes scattered in places around the world, but wanted a last bit saved for burial in the Sanctuary. I can see why; it's exciting to think of one's remains becoming part of a newly growing landscape, actively tended by ardent naturalists.